Image credits: M Holland, CC BY-SA 3.0, and C McAndrew, CC BY-SA 3.0. Changes have been made.

By Archie Turner

The 2010 general election saw an inevitable yet uncertain shift away from the New Labour project. Despite years of high public spending under Tony Blair, the 2008 Financial Crisis left Gordon Brown with a tricky economic dilemma and David Cameron’s vision was considered by some to be the antidote to New Labour’s excessive spending. Cameron’s strong leadership qualities combined with a strong push for strict fiscal policy gave him the illusion of an upper hand in economic discipline and providing more stability for market growth. The Cameron-Osborne principled approach to austerity from 2010 to 2015 saw public spending fall to its lowest share of GDP since the 1940s. This was a desperate attempt to cut the budget deficit; this was seen as desirable because the Conservative Party was concerned about the amount spent on interest payments on this debt which they viewed as an unmanageable fiscal disaster. Austerity disregarded the value of public spending in its ability to create demand, strengthen public services, and reinforce social justice. The aim of austerity was to reduce the budget deficit so the UK could ‘live within its means’ and restore confidence in the economy, but this argument completely disregarded the potential economic benefits from properly allocated investment in public services; specifically the way it could help boost demand and thus help reduce the budget deficit. Furthermore, that argument ignores the moral importance of government spending, as I will show.

The reality was that the deficit did indeed fall but the debt-to-GDP ratio increased (65.1% in May 2010 compared to 80% in July 2016). The reason for this is clear: less demand meant slower growth which meant less revenue – austerity was self-destructive. This is demonstrated clearly by comparison with other G7 countries and their ability to recover from the 2008 Financial Crisis, as the UK recovered the slowest. International economic bodies such as the IMF condemned Austerity for being overdone, suggesting that it slowed recovery after the financial crisis. Evidence of this slowed economic recovery can be seen in the contrast between the USA under Obama and the UK under Cameron. Under Obama, economic stimulus was used, instead of austerity. Subsequently, US GDP grew at around 2-2.5% per year whereas under Cameron, the UK economy grew 1.5% per year between 2010-2015. Indeed, productivity has barely grown – output per worker is lower than in France, Germany, and the US. This was caused by austerity’s underinvestment in infrastructure, skills, and Research & Development, all of which are needed for productivity and economic growth.

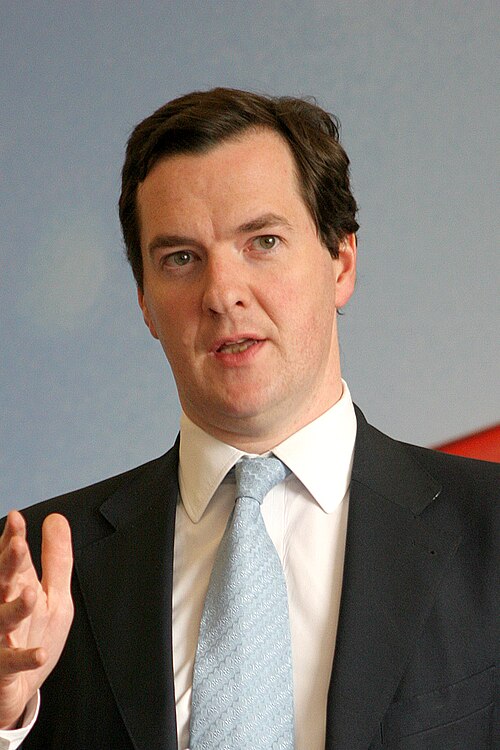

Austerity also affected working people. Let’s not forget that government spending is not just an economic investment in our economy but also a moral investment in our people. Real wages have just only returned to pre-2008 levels, having risen only around 0.1% per year – the worst run of pay stagnation since the Napoleonic wars. This means that people are being paid less for their work now as wages have not kept up with inflation. Economic shocks including the COVID-19 pandemic also played a role in this startling statistic, but austerity played a role in amplifying COVID’s damage too, because the policies that were pursued by David Cameron and his Chancellor, George Osborne, did undeniable damage to public services in this country. From May 2010 to September 2019 the waiting list almost doubled from 2.5 million to 4.6 million: this left the NHS wounded and unprepared for the COVID-19 pandemic. The NHS was therefore unable to help the most vulnerable and desperate in society. If we shift away from the numbers briefly, there is a philosophical argument to be made that what the government did was also an immoral hindrance to the lives of millions of people: people that needed urgent medical care, employment, and a proper education were left on their knees. Services such as the NHS allow for citizens to receive urgent medical care, schools educate the next generation to enter the workforce, and welfare kept many above water – austerity risked damaging all these tax funded services and so as a result, left these institutions less reliable, more unequal, and vulnerable to crises such as COVID-19.

The boys in blue were supposed to bring stability, improve the economy, and put more money into the pocket of the working man. They have done none of those things, and austerity was the driving force of that poor performance.

To be clear, austerity was an entirely avoidable evil. Evidence shows that well-targeted investment boosts growth more than cuts. So fiscal rules should have allowed borrowing for investment in infrastructure and green energy, thus promoting industry and improving the economy. Indeed, the Bank of England’s interest rates were incredibly low post-financial crisis, often sitting at around 0.5%; this gave the Tories an opportunity to borrow with low interest and invest in the economy, instead they chose austerity, which slowed economic growth. As previously mentioned, countries such as the US and Germany had greater economic recoveries than the UK due to their intense focus on investment rather than cuts to public services. A study conducted by the World Bank found that the average multiplier on public investment was 1.5x that of the input. Therefore, if borrowing costs were 1%, as they were in 2009, investment would still create larger amounts of government revenue than the cost of debt interest repayments. Mark Carney, former Governor of the Bank of Canada and the Bank of England (and the current Prime Minister of Canada), warned that austerity subtracted roughly 1% of demand per year and Lord Skidelsky said that it made the British economy 6% smaller, costing around £125 billion. Of course, public spending could have been £540 billion higher without harming the debt trajectory if pairing spending increases had been paired with tax rises, as the Progressive Economy Forum notes. Naturally, Osbornite Conservative ideology could never have accepted this, despite the benefits it would have brought to the economy and the working man. Regardless, this all shows that austerity was entirely unnecessary.

Conclusion: next steps

The failure of austerity looms large on today’s political landscape. Crippling public services and a poor economic record have put the Conservative Party in a dire electoral situation, with very limited media coverage and a lack of clear social and economic policy. Austerity thus has weakened the public’s trust in the Tories.

Labour are attempting to regain the trust of the British people. But one problem they face is in Rachel Reeves’ strict fiscal policy, which echoes the Thatcherite conceptualisation of Government spending as a household budget, in which all spending has to be accounted for and there is very little (or indeed no) willingness to borrow; Reeves’s “iron clad fiscal rules” limit borrowing, thus limiting investment – the exact same mistake that austerity makes. If Labour ditched this idea of extremely disciplined – Thatcherite – fiscal policy, they could invest more money into the economy with a higher Return on Investment (ROI) than the cost that the higher interest rates would take away from the economy. Yet, with the unpredictable political climate of today, politicians may be sceptical about increasing the national debt. However, from what we’ve seen with President Obama, running a budget deficit can inspire growth – and in an era of economic stagnation, growth is exactly what this country needs. This approach would give Labour a chance at economic success without tax rises. If Labour doesn’t go down this road and instead increases taxes in their Autumn budget, there will be a decrease in electoral favourability and Labour’s reputation as a “tax and spend” party will be reborn. Rachael Reeves’ economic plan echoes the argument which led to austerity, following the same basic principles in which over-borrowing was seen as fiscally incompetent. However, a more demand-driven approach to the government’s economic plan would allow for higher public expenditure and would finally bury this ludicrous idea of austerity. The lesson is that the government must learn from the failure of the previous austerity policies that resulted in a high GDP-debt ratio as well as tax rises due to a drop in demand for goods and services.

Leave a comment