Image credits: P. Nasarow and N. Gereljuk, and Roland Zumbuehl. CC BY-SA 3.0

By Andrew Crellin

It is we who plowed the prairies, built the cities where they trade

Dug the mines and built the workshops, endless miles of railroad laid

Now we stand outcast and starving midst the wonders we have made

But the union makes us strong

[…]

They have taken untold millions that they never toiled to earn

But without our brain and muscle not a single wheel can turn

We can break their haughty power, gain our freedom when we learn

That the union makes us strong

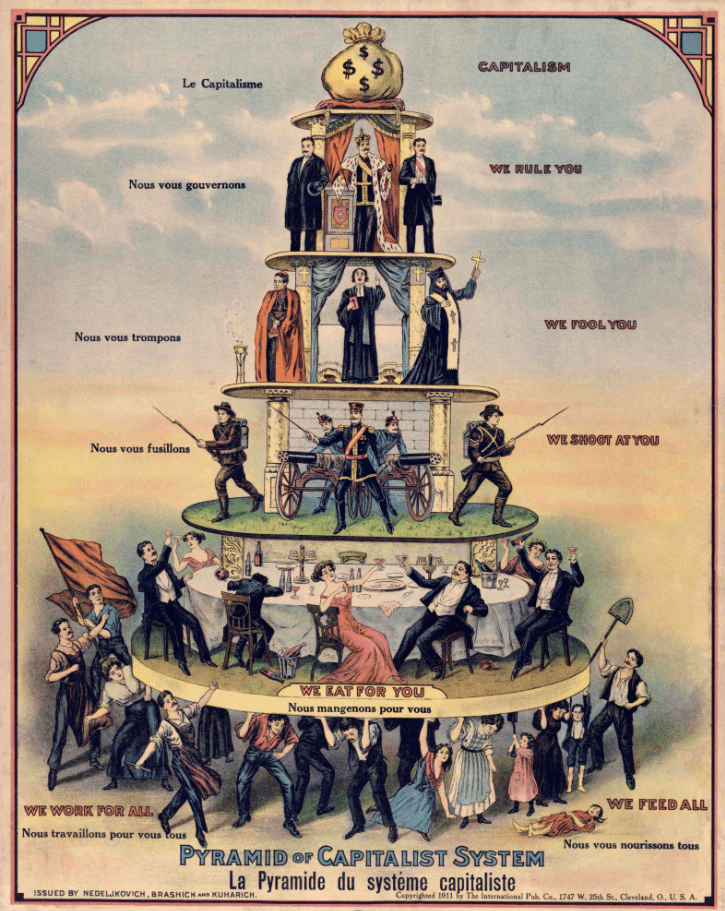

The lines underlined, from the American workers’ song Solidarity Forever, are at once very Marxist and distinctly un-Marxist. On the one hand, they capture succinctly the phenomenon Marxists call exploitation: a systemic disproportionality between work performed and reward received by workers under capitalism. On the other hand, those lines express a view alien to mainstream Marxist theory but common among socialists, including popular depictions of Marxism. That is, they emotively imply that exploitation is wrong – in the sense of being unjust, constituting a maldistribution of the benefits and burdens of social cooperation – and that this wrongness gives reason to struggle against it (in this song’s case, to join a union). This incoherence between the significance of the injustice of exploitation in motivating socialists and popular Marxists and Marxist theory’s arguments against that view is the focus of this article.

In this article, I draw on the insights of the iconoclastic Analytical Marxist tradition to highlight inadequacies in four anti-justice arguments found in mainstream Marxist thought. As such, my argument is that socialists and popular Marxists are right to be concerned with exploitation’s (in)justice because the anti-justice arguments fail. To be clear, my argument is that Marxists (and Marx himself, perhaps) should think of exploitation as wrong. Before that, I introduce the mainstream Marxist view on exploitation and then introduce the Analytical tradition. In the course of this article, then, I hope to demonstrate a key virtue of Analytical Marxism: the depth of its insight into interesting normative questions.

What is exploitation’s role in mainstream Marxist theory?

As indicated, exploitation is a technical term in Marx’s work. While earlier I described it as disproportionality between workers and capitalists, the crucial point is that this entails a transfer of value from workers to capitalists. In short, workers are exploited when they produce goods of value x, while being paid a wage y, where y<x, and capitalists keep the difference (that is, they receive z, where z=x-y). This difference is called Surplus Value.

Workers are exploitable, Marx says, because while they are theoretically free from the domination of the upper classes, they are not free to access the means of production. They thus must accept work to survive. Marx sardonically calls the worker doubly free: free to choose their work, but free from the means of production. Initially, Marx claims, the separation of the worker from the means of production occurred by bloody “Original Expropriation”, where workers were violently driven from the land. This is maintained, Marx argues, by capitalists reinvesting surplus value into labour-saving machinery, thus creating an “Industrial Reserve Army” of unemployed workers. Non-access to the means of production allows capitalists to pay workers the absolute minimum wage possible – more-or-less equal to what a worker needs to survive – allowing the capitalist to pocket surplus value. They must take the surplus value, Marx says, as it enables them to reinvest in more productive processes. Without reinvestment, they will lose in market competition.

In Marx’s analysis, there is a great irony to this process. Marx argues that the worker is the only part of the system which generates profit, that can produce more value. That is, a worker needs fewer goods to survive than he can produce – this is a key part of Marx’s famous Labour Theory of Value. So, when capitalists implement labour-saving technologies (as they must) profitability must fall in the long run. This declining rate of profit leads to innumerable crises which eventually sink the capitalist system.

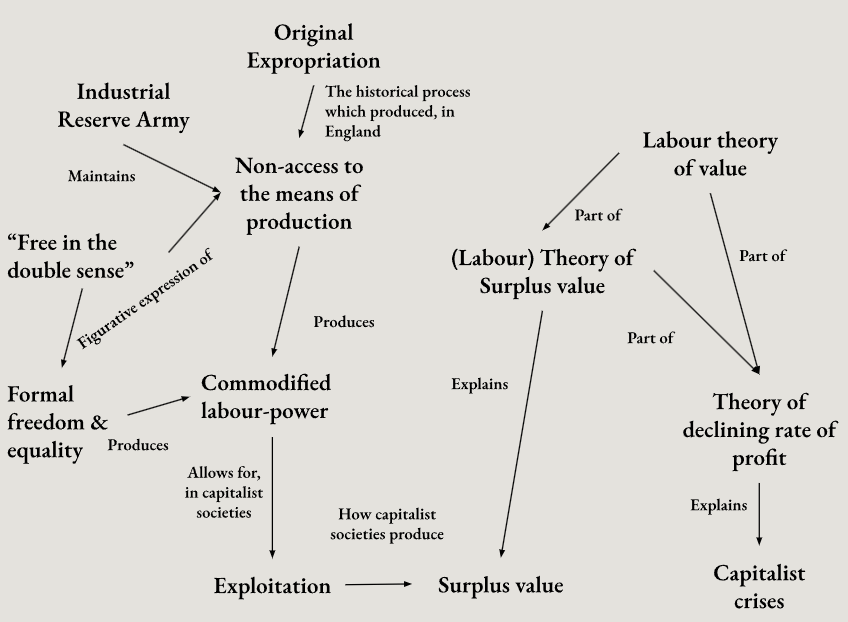

For clarity, the relationship between the ideas sketched above is shown in the following chart:

Upon inspection, it is easy to understand why this part of Marxist theory appeals to those unhappy with today’s society: capitalism, in Marx’s theory, is rotten to the core – exploitative and doomed. While many Marxists use that label to identify with revolutionaries of the 20th century – such as Lenin, Castro, or Mao – surely the centrality of the charge of exploitation plays a role too, as an explication of a fundamental anti-capitalist intuition.

However, as I indicated in the introduction, the mainstream Marxist view does not take the same normative implications from the concept of exploitation which its popular interpretations do. In short, to mainstream Marxists, exploitation is not morally wrong. While many Marxists accept that Marx thought capitalism overall was bad, particularly for workers – this is the so-called Marxist Humanist view – injustice is not considered a suitably-Marxist critique of capitalism. In other words, the criticism is that capitalism destroys the human spirit, not that it mis-distributes the benefits and burdens of social cooperation. It is this anti-justice view which this article aims to tackle.

The four anti-justice arguments I will address are as follows: argument one argues for a non-relative concept of justice, two argues that justice does not capture what Marx wants us to be concerned with, three argues that justice is meaningless as a motivator, and four argues that considering exploitation’s injustice is incompatible with the Marxist commitment to communism. Before tackling those arguments, let me introduce a group of Marxist scholars who took the concept of justice seriously. It is their arguments I will use to build my case for a concern with justice, and the injustice of exploitation.

Analytical Marxism

Beginning in the 1970s, Analytical Marxism combed through Marx’s work with the aim of salvaging the good and throwing out the bad. Their goal was to bring to bear on Marxism the tools developed in mainstream social science and philosophy since Marx’s death: methodological individualism, and analytic philosophy. The former, made famous in neoclassical economics, is the idea that explanations for macro-level phenomena must be grounded in micro-level, individual-focused, behaviour. The latter involved a concern for tight arguments and thus involved careful use of language and close analysis to draw distinctions within concepts. As such, some Analytical Marxist work involved finding new defences for old Marxist concepts while other work involved throwing away what simply could not pass under the new standards of academic rigour.

Significant parts of the Analytical Marxist project were inspired by dissatisfaction with developments in mainstream Marxism, such as Althusserianism. G.A. Cohen, one of the three central figures of Analytical Marxism, described Althusserianism as a set of ideas which were either true but trivial, or fascinating but false. Only by their incredibly unclear presentation did they appear fascinating and true. Cohen, along with the other two central members of the tradition, John Roemer and Jon Elster, formed the so-called No Bullshit Marxist Group (also known as the September Group) of academics to work on these ideas. Nevertheless, it was with this critical eye that they dissected Marxism, including even Marx himself.

Analytical Marxism’s prevalence has waned since the 1990s, though there are still scholars influenced by the tradition today: most famously the political philosophers Nicholas Vrousalis, Tommie Shelby, and Charles Mills. To a certain extent, Analytical Marxism simply ran out of material to analyse. However, the tradition was also threatened on all sides. From the perspective of mainstream Marxism, the use of non-Marxist methods threatened to remove valuable tools of analysis and assimilate Marxism into so-called bourgeois social science. On the other hand, some mainstream social scientists and philosophers dismissed engagement with Marx altogether while the aforementioned assimilation threatened the distinctiveness of the tradition, such that scholars today do work previously termed Analytical Marxist without identifying with the moniker. For example, Cohen’s later work in political philosophy had significant crossover with left-wing liberalism and Roemer’s later work on institution design extensively uses mainstream tools of microeconomics (such as game theory). All in all, Analytical Marxism is threatened with extinction.

However, I would propose that some of their best work was on the concept of exploitation. Indeed, theorising exploitation remains fertile ground in political philosophy – a key legacy of this tradition, I would argue. Picking up the tools left, I will now tackle the four Marxist arguments introduced earlier. In doing so, I hope to show there is still much in terms of insight that we can learn from the Analytical Marxists.

Argument 1: Exploitation is not unjust

First, Marx explicitly denies that exploitation is unjust. In Capital, he says the ability for capitalists to exploit workers is “a piece of good luck for the [capitalist], but by no means an injustice to the [worker]”. Indeed, he asserts that, since the worker is paid the market rate for their labour, the worker is not underpaid – so, workers’ exploitation is actually just.

These peculiar comments make more sense when we consider that Marx, as demonstrated in his Critique of the Gotha Programme, considered notions of right and wrong as relativised to particular historical periods, defined by their mode of production. As to the question of the fairness of workers’ (exploited) pay, he says “is it not, in fact, the only fair distribution on the basis of the present-day mode of production?” To back this up, he asserts that “legal relations arise from economic ones” and “[justice] can never be higher than the economic structure of society and its cultural development conditioned thereby”. In other words, what we consider just is simply what capitalism requires to function. This point is made concrete in The German Ideology, where Marx argues that morality, including our view of justice, is a form of ideology, and so arises from economic structures. So, exploitation is perfectly just, in the sense that justice (currently) refers to capitalist norms, and exploitation contravenes none of these (since the worker is paid the market rate for their labour).

But, if Marx believed that, why did he call it exploitation? This is Cohen’s, Elster’s, and Geras’ critique. As Elster asks: if exploitation is not in any way wrongful, why use such a value-laden term to refer to it? As Cohen notes, Marx used terms like theft and embezzlement to refer to exploitation. Geras also adds that Marx calls surplus value, the capitalist’s revenue from exploitation, loot. Theft in particular is so conceptually close to injustice that it is hard to see any other interpretation as reasonable. Marx’s use of terms like theft, embezzlement, and, of course, exploitation to refer to paying workers just seems to imply a sense of wrongness. There is, then, a great contradiction in Marx’s ideas. As Cohen notes, if Marx believed:

- Capitalism is not unjust by capitalist standards

And

- Capitalism is unjust

Then he had to believe

- Capitalism is unjust by at least one non-capitalist standard

Therefore, affirming that there are non-capitalist standards of justice. This, of course, stands in direct contradiction to his view that justice is constrained by social development.

How can we square this? In short, Geras suggests we introduce a distinction between people’s ideas of justice and the concept of justice. We can say, then, that the former is influenced by the economic structure but not the latter. As such, while capitalism is indeed unjust, it does not appear to be because living within it generates (through the processes of delusion and ideology) the feeling it is perfectly just. Of course, that Marx can reveal the ideological delusions and show us the “mere semblance” and only “apparent exchange” of labour for wages (which just appears equal) shows that not everyone’s idea of justice is relative. But, in any case, it is entirely coherent to believe that popular views of justice are relative, and to believe that there is a universal concept of justice. Put simply, there is nothing wrong with saying that we can get things wrong. As an analogy, consider this view in terms of laws of physics: people get different ideas on what the laws of physics are, based on the evidence available to them – which is perhaps determined by their society’s level of advancement in the same way Marx believes ideas of justice are – but this surely doesn’t invalidate the universality of the actual laws of physics (whatever they are).

As such, Marx’s (albeit dubitable) assertion that ideas of justice are tied to social development does not entail that justice is tied to social development. This allows us to synthesise Marx’s insights, and continue calling the transfer of surplus value exploitation, that is, unjust.

Argument 2: Worrying about exploitation’s justice is counter-revolutionary

Another argument Marx advances against caring about exploitation’s injustice is that to do so is counter-revolutionary. This can be found in the Critique of the Gotha Programme. Here, Marx comments on some other socialists’ proposal, to ‘fairly’ distribute the product of labour, so give it all to the labourers themselves – in other words, abolish exploitation. In response, he argues that charging exploitation with injustice would merely question the distribution of the ‘means of consumption’ – to argue that the worker deserves more money to spend. Yet, he argues, altering the distribution of income would never go far enough: capitalism is more than a distributive system, but a productive one too. The injustice of exploitation, then, is irrelevant: it is just the necessary consequence of the capitalist system. Being concerned with exploitation’s injustice is a distraction, he concludes, which leads to mere counter-revolutionary reformism. This argument, alleging that being concerned with distributive justice means seeking a redistribution of wealth under capitalism, has a shadow in contemporary Marxist thought: many today publicly decry social-democratic governments as going not far enough for similar reasons. Indeed, perhaps this argument captures precisely how Solidarity Forever misses the Marxist mark. That song calls for joining a union – and what do unions do but barter over pay?

This argument, however, is deeply confused: it seems to misunderstand what justice is, as a value. As introduced earlier, it is a concern with the distribution of benefits and burdens of society. Exploitation is thus proposed as a misdistribution of the benefits and burdens of labouring: the labourer suffers the burdens but receives an intuitively insufficient reward. But, as Geras notes, the subject matter of justice does not have to stop at income and wealth. The distribution of free time, for example, would also be a meaningful subject of justice. Indeed, Geras points out, Marx seemed to be aware of this: in The Grundrisse Marx says that capitalists “usurp the free time created by workers for society”. Recall my discussion of argument one to see why “usurp” implies an injustice. In much the same way, then, the distribution of the means of production in society could be the subject of justice. Thus, to be concerned with justice does not preclude being concerned with altering the mode of production, the economic structure of society.

But what if Marx meant that being concerned with exploitation’s injustice pulls against being concerned with the distribution of the means of production? It seems to me, though, that Marx’s comment here refutes the only way to get that conclusion. If it were the case that exploitation could be abolished without altering the economic structure, then socialists only concerned with ending exploitation could indeed be counter-revolutionary reformists. But Marx, in saying that exploitation is a necessary consequence of the economic structure of capitalism, refutes that claim. As such, Marx’s conclusion – that one should abandon a concern with exploitation’s injustice – is bizarre.

For clarity, let me put this as propositions:

- Exploitation should be abolished (says the Gotha Programme)

- Exploitation cannot be abolished without abolishing capitalism (says Marx)

What is the appropriate conclusion? Surely:

- Capitalism should be abolished

So, the commitment to abolishing exploitation leads, once combined with Marx’s insight as to exploitation’s necessity under capitalism, to a commitment to abolish capitalism. It does not, as is hopefully abundantly clear, lead to a commitment not to abolish capitalism. To get that view, you would need to say:

- Capitalism cannot be abolished (at least, not right away)

- Ought Implies Can; you have no obligation to do what you cannot do

These two propositions give you:

- It is not the case that capitalism should be abolished

Clearly, (6) and (9) are in tension – they are contradictory statements, (p) and (¬p). Assuming the truth of (5), if you believe (9) more than you believe (6), you would indeed have to abandon (4). It is entirely possible that this is what Marx meant to say against the so-called reformists. Given the famousness of (8) as a Kantian principle, I suspect Marx was aware of it. As such, I will discuss one reason Marx had for believing something like (7) in the next section.

However, to conclude on the tension between revolution and justice: Marx’s argument, as he states it, does not defend its conclusion. Justice is a more expansive concept than Marx believed, and this allows a concern with exploitation’s injustice to escape the charge of reformism. If exploitation is unjust, and exploitation is the necessary consequence of capitalism, then capitalism is unjust too. No reformism follows from calling exploitation unjust. Returning to Solidarity Forever, it is of note that that piece was originally written for the union called the “Industrial Workers of the World”. While a union, they were a revolutionary union: their goal, clearly, was more than just fair pay. It seems, then, to struggle against unfair pay is not necessarily anti-revolutionary: in theory or in practice.

Argument 3: Motivations from justice are causally unnecessary

Mainstream Marxists also argue that justice, as a value, is to be ignored because norms are causally unnecessary: the revolution will occur as a result of material forces, not moral motivation. As such, discussion of abolishing capitalism by political manifesto – as the so-called reformists in argument 2 proposed – is nonsense. This argument gives grounds, then, to believe a version of (7). This view can definitely be seen in Marx’s writings – such as in The German Ideology, where communism is referred to as real rather than an ideal, and in The Civil War in France, where he says socialist revolutionaries have “no ideals to realise” but instead will simply “set free elements of the new society with which old collapsing bourgeois society is itself pregnant”. This argument was, however, significantly elevated by his intellectual co-conspirator Engels when he started the tradition of distinguishing Marxist “scientific” socialism from pre-Marx “utopian” socialism. By this, it is meant that the coming fall of capitalism is a matter of fact, not an ideal of justice. Modern Marxists use this argument to conclude that capitalism is doomed regardless of whether the revolutionaries view it wrong. In Michael Heinrich’s Introduction to the Three Volumes of Karl Marx’s Capital, Marx is said not to propose a moral critique that would inspire the working-class through moral motivation. Instead, Marx is said to simply reveal workers’ mistreatment – since their self-interest will do the rest.

Cohen raises a key objection to the idea that moral motivation is unneeded. Previously, in the heyday of socialist theory, the working class were the majority of society, hungry, unfairly compensated for their work, yet indispensable for producing the vast majority of society’s wealth. However, today very few people are in absolute poverty in the Western World, and even worldwide extreme deprivation is in decline. Furthermore, the Western working class has disintegrated and there is a global shift towards services-based economies. So, of those four once-true facts, the only one which remains possible to be true is unfair compensation. If workers do not recognise the moral problem, they surely will not revolt. Indeed, workers in different sectors, with often-contradictory goals (where they could sell each other out for their own gains) and spread across the globe – with very different cultures, making mutual recognition difficult – would have to cooperate. It is thus hard to see how moral motivation is not required, in this contemporary context. Geras has reinterpreted the objection to the purpose of moral motivation in a much more productive way than Engels did – as an objection to pure moralising. Talk is indeed cheap, and activism must go beyond it to be effective. Just ends are not often achieved through moral philosophising. But, moral motivation may be needed today to inspire actions to achieve revolutionary ends. More must be said, of course, to show that ideas of justice can motivate revolutionary change – to properly challenge (7). But, either way, it seems revolution will not happen without those ideas. Thus, discussions of justice should not be ignored.

Argument 4: Exploitation’s injustice is irrelevant since exploitation is required for communism

The final argument I will consider here is that, since exploitation is needed to achieve communism, and communism is the ultimate goal, any moral qualms with exploitation are to be ignored. This could be said to be a Marxist humanist argument against a concern with justice: beginning from a normative position valuing communism, it disputes the significance of justice – specifically, acting on the proposed injustice of exploitation.

To be clear, communism is a time of ‘mass self-actualisation’, where all can live truly satisfying lives. It is intuitively clear that mass self-actualisation requires more wealth than that seen in pre-capitalist societies, i.e. economic development – if nothing else, to allow for leisure time and goods to consume for enjoyment. In Marxist terminology, it is the productive forces which generate wealth. Thus, the necessity of exploitation for the possibility of communism can be seen in the following propositions:

- Without relative abundance, there can be no mass self-actualisation

- Without developing the productive forces of society, there can be no relative abundance

- Without exploitation, there can be no development of the productive forces

Therefore:

- Without exploitation, there can be no mass self-actualisation

Let us now interpret the normative side of the argument. To do so, consider that this example has similarities with how moral philosophers discuss the concept of genuine moral dilemmas. These are situations where (it at least appears that) you have conflicting moral requirements derived from your commitments to different values. One relevant response in the literature on genuine moral dilemmas has been to argue that, by carefully considering the values in question, it can be revealed that one matters less than the other. The Marxist, then, seems to have conflicting requirements between ending exploitation and bringing about communism. The promoter of this argument suggests that, given a straight conflict between achieving communism at all and ending exploitation, it is clear Marxists are to prioritise the former. Thus, the moral side can be tentatively stated as follows:

- Achieving Mass self-actualisation is the most important obligation

- Obligations from justice call for ending / preventing exploitation

- Therefore, obligations from justice call for preventing mass self-actualisation (given (13))

- Therefore, obligations from justice are to be ignored.

Let us now critique this argument. In short, it is not clear that there is a sharp trade-off between achieving communism and ending exploitation. Then, with this complication, the argument’s position on the balance between the values is considerably less acceptable.

Two things are missing from (10) – (13). First, strictly speaking, it is past exploitation which enables current mass self-actualisation. So, given that communism is a far-off goal, it is likely that the exploited workers are not the self-actualised people, but instead their ancestors. In this sense, then, exploitation is suffered by one generation so a later one can enjoy mass self-actualisation. Second, it is not immediately true that exploitation must occur for there to be a growth in the productive forces. There must be surplus value, the thing that is exploited from workers, as otherwise there would be nothing to save for investment – otherwise, all value produced would be consumed. But not all production of surplus value is exploitation: in a brief comment on the matter in The Critique of the Gotha Programme, Marx seems to suggest that non-exploitative production of surplus value would be possible if the economy was brought under workers’ control. To fill the explanatory gap between the necessity of surplus value and the necessity of exploitation, Marx says the latter is necessary for communism because workers would not impose on themselves sufficient burden to develop the productive forces of society.

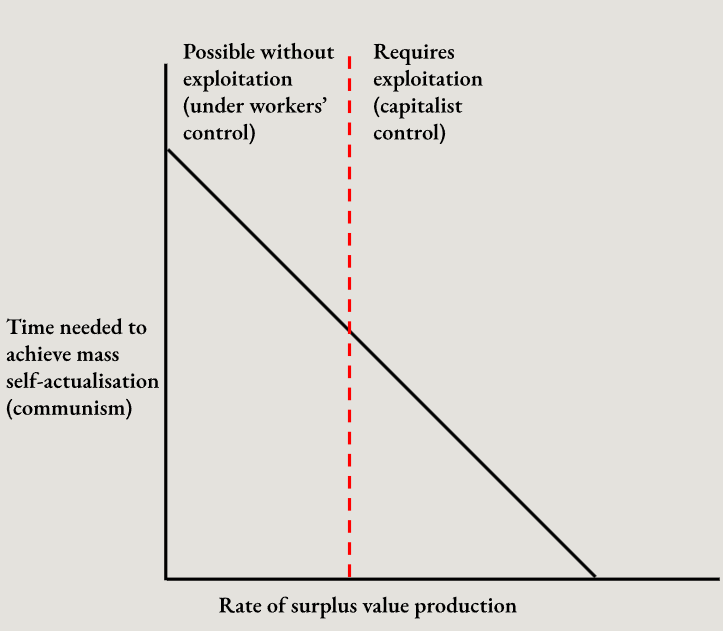

But surely these two points are in tension. If the process of building the productive forces by accruing surplus value occurs across several generations, then the cost to any one generation could be spread out so that no particular generation suffers any great burden. Marx’s statement implies that if no great burden is required, workers could self-impose it. Thus, exploitation is not required for achieving communism. For example, if a 50% rate of surplus value production reduces the workers of one generation to squalor, so can only occur under exploitation (capitalist control), then why not half the rate of surplus value production but take two generations to develop the same total surplus without exploitation (under workers’ control)? This would allow a self-organised society of workers to accrue enough surplus value to reinvest and create the conditions of mass self-actualisation – given that workers can be concerned with benefits to their future generations (and why wouldn’t they be?). Such examples show that a concern for exploitation’s injustice and achieving communism are not necessarily in tension: the dichotomy between achieving communism and abolishing exploitation is thus false. If exploitation is necessary only to raise the rate of surplus value production above what workers would choose autonomously, allowing exploitation represents merely a choice as to the speed of achieving communism. So, why favour quickly achieving communism over ending exploitation?

To be clear, this is now a discussion of theorising a system of moral principles. In such discussions, the dominant methodology is to test different theories against our strongest-held intuitions, our considered judgments, about right and wrong, and to find the theory which best cohere with them. This is what John Rawls calls the method of reflective equilibrium. In that spirit, then, let us test prioritising quickly achieving communism over ending exploitation against some deeply-held intuitions.

The most natural defence would be the utilitarian-esque view that greater gains to some people offset losses to others. However this is deeply counterintuitive. As John Rawls famously argued, it seems to slur benefits and burdens across people, asking that people suffer for others’ satisfaction. Writ large, this view is surely unacceptable: would you hang an innocent person to satisfy a sufficiently large mob? For reasons such as this, the mainstream Marxist view cannot be defended on utilitarian grounds (alone).

You may respond to that comment that we do seem to think losses for some can be outweighed by gains for others in other discussions of intergenerational justice. For example, we likely share the intuition that it is appropriate for us to accept losses in our welfare to reduce the impact we will have on future generations by damaging the climate. After all, you might enjoy driving a gas-guzzler, but you feel it wrong to burden future generations with a destroyed planet. However, our intuition here is actually the opposite of the Marxist view. In the climate change case, we ask a better-off generation to accept a loss so that a worse-off generation may gain. By favouring quickly achieving communism, we ask poorer generations to accept an even greater loss in welfare – by being exploited – for the benefit of making, presumably, better-off generations even better-off is the very opposite. I say that future generations would presumably be better off due to the discussion of argument three, that capitalist exploitation seems to raise living standards. In short, then, prioritising quickly achieving communism over ending exploitation contradicts our intuition of fairness between generations. This counter-intuitiveness suggests we may, therefore, reject it.

In summary, then, it is entirely appropriate for Marxists as communists to care about exploitation’s injustice. There is no absolute tension between achieving communism and reducing, or even ending, exploitation. Achieving communism does not require exploitation, and insisting on a route to communism containing exploitation is indefensible. The practical upshot, then, is that even mainstream Marxists should engage in struggle to reduce exploitation to a minimum, perhaps including the socialisation of surplus value (that is, ending the class domination which makes the extraction of surplus value exploitation). In addition, this should vindicate socialists and popular Marxists: their normative concern with exploitation is defensible.

Conclusion

I have surveyed four Marxist arguments against a concern with justice. We can thus conclude that relativism about justice is inappropriate, being concerned with exploitation’s injustice is not reformist, thinking about justice can be part of bringing about social change, and seeking to bring about communism does not necessarily preclude caring about, and reducing, exploitation. I have used insights by the Analytical Marxists to develop these critiques. I hope this vindicates the tradition, reminding us that their work remains insightful.

I have not, of course, defended the claim that exploitation is indeed unjust. While this topic is too grand for this article’s conclusion it is of note that the Analytical Marxists developed this too. The short answer is that the background conditions enabling exploitation – as discussed in my coverage of argument 2 – are crucial to why it is wrong. For Roemer and Cohen, it is the unequal access to the means of production that is unjust, and hence exploitation is rendered unjust subsequently. On the other hand, Vrousalis has developed a case that it is the capitalists’ control over, and use of the vulnerability of, workers which makes exploitation unjust. Either way, though, the positive thesis – that exploitation is unjust – is defensible. But that is a topic for elsewhere.

In sum, though, it is clear that socialists and popular depictions of Marxism are right to depict exploitation as an injustice – the mainstream Marxist arguments to the contrary are ill-founded.

References and Further Reading

Thank you to the University of York Politics Department’s Kieran Durkin for helpful comments on my understanding of Marxist theory.

An excellent volume of Marx’s writings, containing all that I reference in this article, is: Marx, K. (2000). Selected Writings Second Edition. Mclellan, D. (ed). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Further reading on the tradition of Analytical Marxism as a whole can be found in: Bertram, C. (2008). Analytical Marxism. In Critical Companion to Contemporary Marxism. Bidet, J, and Kouvélakis, S. (eds.). Boston: Brill.

Cohen’s account of his analytical turn can be found in the introduction of: Cohen, G.A. (2000). Karl Marx’s Theory of History, a Defence. Oxford: Clarendon Press. And: Cohen, G. A. (2013). Complete Bullshit. In M. Otsuka (Ed.), Finding Oneself in the Other. Princeton University Press. pp.94-114

Elster’s comments on justice can be found in chapter 4 of: Elster, J. (1985). Making Sense of Marx. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Geras’ comments on justice can be found in: Geras, N. (1985). The Controversy About Marx and Justice. New Left Review, No.150 (150), 47–85.

Cohen’s comment on how Marx must affirm a non-relative standard of justice can be found in: Cohen, G. A. (1983). Review of Karl Marx, by A. W. Wood. Mind, 92(367), 440–445.

Cohen’s comment on the four characteristics of the working class can be found in: Cohen, G. A. (1994). Equality as Fact and as Norm: Reflections on the (partial) Demise of Marxism. Theoria: A Journal of Social and Political Theory, 83/84, 1–11. And also the introduction of: Cohen, G.A. (1995) Self-Ownership, Freedom, and Equality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

The discussion of, and my response to, argument four are inspired by Cohen’s incredibly brief comments in: Cohen, G.A. (1988). Freedom, Justice, and Capitalism. In his History, Labour, and Freedom: Themes from Marx. Oxford: Clarendon Press. And: Cohen, G. A. (1986) ‘Peter Mew on Justice and Capitalism’, Inquiry, 29(1–4), 315–323. See also: Mew, P. (1986) ‘G. A. Cohen on Freedom, Justice, and Capitalism’, Inquiry, 29(1–4), 305–313. Discussion of the necessity of exploitation can be found in section 7 of chapter 7 of Cohen, G.A. (2000). Karl Marx’s Theory of History, a Defence. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Leave a comment