Image Credit: Nikolett Emmert

By James Gannon

Throughout history, political leaders have frequently intertwined religion with their rule, using it as a tool to consolidate power and establish legitimacy. From ancient god-kings to modern strongmen, the fusion of religion and politics has often created a cult of personality around leaders. This article examines three case studies: François “Papa Doc” Duvalier in Haiti, the Kim dynasty in North Korea, and later we will apply the findings in those cases to Donald Trump’s MAGA movement in the United States, to see if it qualifies as a cult of personality. While the melding of religion and personality has created near-comical results, it has real-world consequences for the rest of us.

Why Do Leaders Embrace Religion?

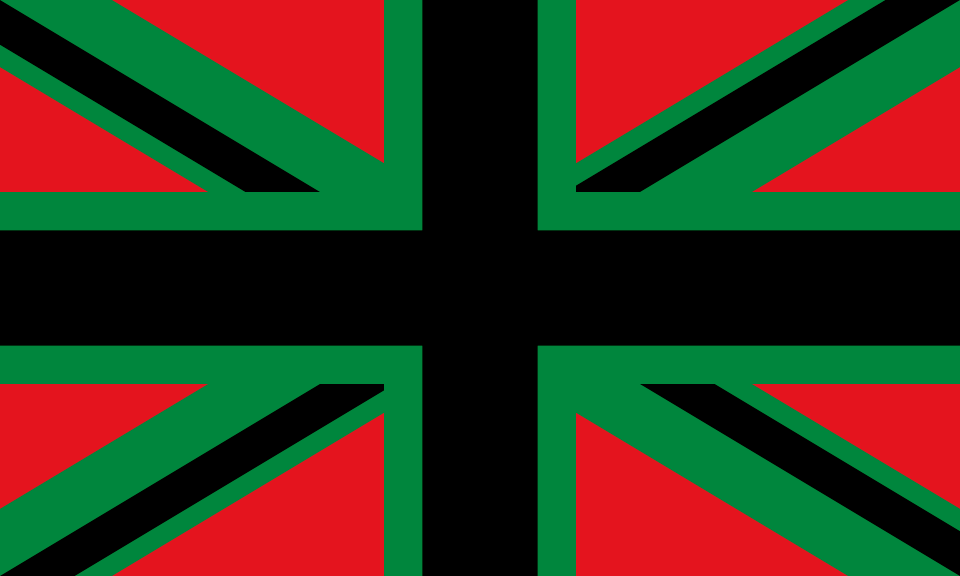

Religion has long been a potent political tool. By aligning themselves with divine authority, leaders can neutralise religious opposition and position themselves as chosen saviours. This strategy not only provides legitimacy but also creates a framework for succession, as seen in monarchies and dynastic regimes. Historically, rulers such as medieval European kings invoked the “divine right” to justify their reigns. The British state itself is built upon a legion of revered monarchs from William the Conqueror, the Tudors, and even now to the presiding Royal Family. While modern-day Britain’s religious roots have been greatly trimmed, and the Royal Family reduced to — in the words of Olivia Colman in season 4 of The Crown — “Tribal leaders in eccentric gowns”, the legacy of once infamously divine personality cults have defined our history for centuries.

Yet, we are not the only ones: cast your gaze out to the rest of Europe, and the world, and you’ll find most of humanity has at some point been moulded by the rule of religious zealots, by men and women who claimed to be the mouthpiece for a higher power. But how has religion enabled these figures throughout history, and in the present day?

To the modern leader, embracing religion has many benefits. First and foremost, if you can’t beat your enemy, join them. Politicians, of all the people in the world, are mired in sin, and claiming to be part of a higher group serves to deflect much of the moral criticisms people in power face. But also, religious institutions, depending on the country, can wield profound influence, presenting rulers with the dilemma of having to bend these institutions or be bent themselves. From Henry VIII beginning the Protestant Reformation, to the Nazi party bastardising the German church, many leaders and states throughout time have amalgamated their base with religious elements to bolster their strength. One of the caveats of such a tactic is that the leaders themselves become divinely ordained: God’s chosen one. What often follows is the emergence of dynasticism, but for many dictators and strongmen, this is a blessing in disguise, as hereditary rule is the ultimate solution to a succession crisis.

Papa Doc Duvalier and Vodou: The Case of Haiti

François “Papa Doc” Duvalier ruled Haiti from 1957 until he died in 1971, blending Vodou’s mysticism with authoritarianism to create a powerful cult of personality. At the beginning of his rule, Duvalier emerged as a compassionate figure in Haitian politics, known for treating rebel groups in Haiti’s rural areas during his time as a doctor, though as he ascended to power and his rule extended, so too did his repression. With his militia—the Tonton Macoute—butchering swathes of his subjects, Duvalier began to embrace the cult of personality that defined his reign. Following a stroke in the later years of his reign, Duvalier emerged as a different man, with the episode turning him more paranoid and delusional. Duvalier, convinced by his own mania, portrayed himself as the physical embodiment of Haiti and claimed divine connections through Vodou spirits. He deliberately modelled his appearance on Baron Samedi, a Vodou spirit revered as the guardian of graveyards, further enhancing his aura of invincibility. Rumours surrounding Duvalier were said to stretch from eating his rival’s children to being able to speak to the dead, all of which served to cement his reputation of repression.

Furthermore, Duvalier’s propaganda machine reinforced his godlike status. One infamous image depicted Jesus Christ placing a hand on Duvalier’s shoulder with the caption, “I have chosen him”. In 1964, he published a catechism that replaced references to God with his name. These tactics allowed him to consolidate power and even secure the presidency for his son, Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier. However, this dynastic succession was short-lived; Baby Doc was overthrown in 1986, demonstrating that such cults can crumble without sustained legitimacy. But from Papa Doc, we learn the chief benefit of the cult of religious personality, and that was the ability to strike fear into your enemy’s hearts… assuming you haven’t already cut them out and eaten them.

The Kim Dynasty and Juche Communism: The Case of North Korea

In North Korea, the Kim dynasty has elevated its leaders to near-divine status through its Juche ideology—a blend of Marxism-Leninism and Korean nationalism. Kim Il Sung established Juche in the 1960s as North Korea’s guiding principle, emphasizing self-reliance and the indispensability of a “Great Leader”. Over time, Juche evolved into a quasi-religion, with Kim Il Sung portrayed as the father of the nation and his successors as divinely ordained leaders. Jucheism is renowned for its bizarre mythology, with Kim Il Sung being the worst offender: it is alleged that Kim Jong Il was born on Mount Paektu (his actual birth was in 1941 in the Soviet Union) and that his birth was marked by a swallow, caused winter to change to spring, a star to form and light the sky, and a double rainbow spontaneously appeared. Now, admittedly, this rip-off nativity story is quite amusing, and to the Western mind must seem completely ludicrous, but considering it was told in a totalitarian system where the Kims are viewed as Gods, then these depictions are taken as seriously as the aforementioned nativity.

American historian Charles K. Armstrong has described Juche as transforming familial relationships into national ones, with the Kims embodying paternal authority over their “children”, the North Korean people. This ideological framework ensures dynastic succession while maintaining an unassailable grip on power, and as a result, the Kim dynasty remains intact today, illustrating how deeply ingrained such cults can become when supported by state propaganda and institutionalized ideology, but builds upon the failures of other dictatorships (such as Duvalier), in being able to expertly craft an invincible line of succession.

Donald Trump and Evangelical Christianity: United States

Donald Trump’s presidency marked a significant convergence between evangelical Christianity and political nationalism, giving rise to a movement that some argue bears the hallmarks of a quasi-religious cult. White evangelicals, in particular, formed the bedrock of Trump’s support, with 81% voting for him in 2016. This overwhelming loyalty stemmed from a combination of Christian nationalism — a belief that America is divinely ordained as a Christian nation — and fears of losing cultural dominance in an increasingly diverse and secular society. Trump skillfully tapped into these anxieties, positioning himself as the champion of their values and the defender of their way of life.

What makes this alignment particularly striking is Trump’s ability to present himself as a messianic figure, despite his moral bankruptcy. At the 2016 Republican National Convention, Trump famously declared, “I alone can fix it”, a statement that elevated him above traditional institutions, leaders, and even divine providence in the eyes of his supporters. This sort of rhetoric not only appeals to evangelical fears but also fuses religious imagery with nationalist themes, creating a powerful narrative that casts Trump as both the saviour and protector of conservative Christian values; in merging himself as the lone saviour of a nation, you begin to see the parallels with other schools of thought such as Jucheism.

Throughout his presidency and beyond, Trump’s use of evangelical rhetoric deepened this connection. He frequently invoked religious language, framed political opponents as enemies of faith and freedom, and surrounded himself with high-profile evangelical leaders who reinforced his image as God’s chosen leader. Some supporters even went so far as to describe him in biblical terms, comparing him to figures like King David or Cyrus the Great — flawed but divinely anointed leaders tasked with fulfilling God’s will. This perception has turned Trump into more than just a political figure for many; he has become a symbol of divine intervention in American politics, and with such imagery, we once again find similarities with men such as Duvalier who once presented themselves as the “anointed” ones.

The quasi-religious nature of the MAGA movement is further evident in its cult-like devotion to Trump. His supporters often view criticism or legal challenges against him as attacks on their own identity or faith. For instance, Trump’s multiple indictments have been framed by some within the movement as evidence of persecution akin to that faced by early Christians or biblical prophets. This narrative strengthens their resolve and deepens their emotional investment in Trump as a leader who is not just fighting for political power but for their very survival in a changing cultural landscape.

Interestingly, some within the MAGA movement have even speculated about dynastic ambitions for Trump’s family, with occasional references to his youngest son Barron as a potential future leader. This idea evokes comparisons to regimes like those in North Korea or Haiti, where leadership is passed down within families to sustain ideological continuity. However, while such speculation highlights the depth of devotion among some supporters, it also underscores one of the movement’s greatest vulnerabilities: its reliance on Trump’s singular personality. Unlike institutionalized ideologies such as Juche in North Korea or religious movements with established doctrines and hierarchies, MAGA lacks a clear successor or structural framework to ensure its survival beyond Trump himself.

As Trump ages and no obvious successor emerges within his family or inner circle, questions about the movement’s longevity become increasingly pressing. Can MAGA outlive its founder? Or will it fade without his charismatic leadership? While the evangelical base that forms MAGA’s core will likely persist as a political force within the Republican Party, it is unclear whether they will transfer their loyalty to another figure or whether Trump’s unique blend of charisma and messaging can ever be replicated.

Moreover, while MAGA wields significant influence within conservative circles and dominates much of the Republican Party’s platform, it does not represent the majority of Americans. The movement’s reliance on grievance politics and cultural nostalgia appeals strongly to its base but alienates many others across the political spectrum. This limits its broader electoral power and raises questions about whether it can sustain itself in an increasingly diverse and progressive society. In the end, none of us can predict the future, but I speak for most of us when I say I hope to God Trump doesn’t pull a Papa Doc and proclaim himself to be the Floridian Deity of Golf Courses (fun fact: he buried his wife on his golf course to make it tax-exempt).

Leave a comment